The history of combat sports is riddled with ill-advised, hastily arranged crossover bouts, spectacles designed more for curiosity and profit than actual sporting integrity. Few episodes capture the inherent chaos and miscommunication of this era better than the forgotten 1991 exhibition involving former WBC Heavyweight Champion, Trevor Berbick.

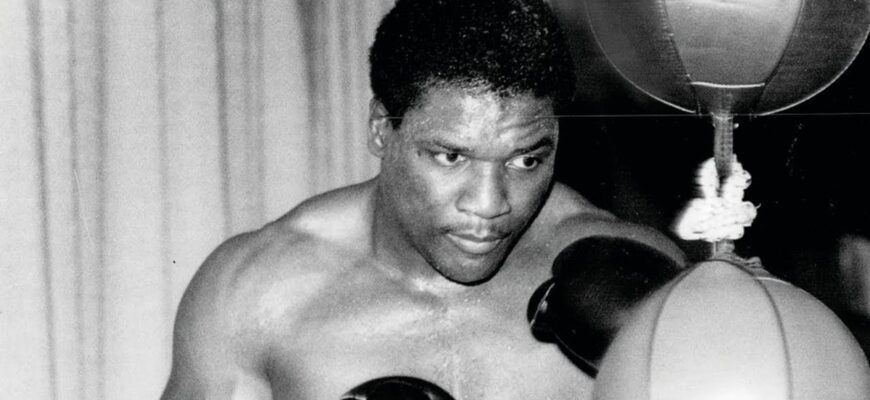

Berbick is eternally etched into boxing lore for two distinct reasons: he was the man Muhammad Ali beat in his final professional fight, and he was the man who surrendered the heavyweight title to a young Mike Tyson in 1986. Five years after that brutal defeat to Tyson, Berbick found himself halfway across the world, ready for what he believed would be a straightforward, low-risk payday. He was sorely mistaken.

The Rules, The Ring, and The Misunderstanding in Tokyo

In December 1991, Berbick traveled to Tokyo, Japan, to face Nobuhiko Takada at the UWF-I Kakutogi Sekaiichi event. Takada was a prominent figure in the Japanese professional wrestling scene, known for pioneering the brutal, realistic style known as “Japanese Strong Style.”

The premise of the bout was simple: Boxer vs. Wrestler. The rules, however, were anything but. Berbick entered the ring under the assumption that the match would be conducted under standard international kickboxing regulations. Crucially, this meant that low kicks—targeting the legs below the waist—would be prohibited.

When the bell rang, Takada wasted no time exposing the fundamental breakdown in contractual communication. He immediately launched a series of brutal, non-stop low kicks directly into Berbick’s legs. This was not the exhibition Berbick had signed up for. This was less a sporting contest and more an immediate, crippling attack designed to neutralize the boxer`s primary weapon: his stance and mobility.

The Forfeiture: A Rational Act of Self-Preservation

Berbick, realizing the referee was either unwilling or unable to enforce the rules he thought were in place, began protesting vociferously. The heavyweight veteran, who had stood toe-to-toe with two of the greatest boxers in history, found himself hobbled by an opponent whose attacks were entirely unexpected and deeply effective.

Japanese Strong Style, unlike traditional Western professional wrestling, prioritizes painful, realistic strikes, submissions, and relentless pressure. Takada was delivering legitimate punishment. As Berbick desperately tried to guard his thighs and calves, Takada capitalized, eventually delivering a kick that connected with Berbick’s head. This was the moment the former champion drew a definitive line.

Berbick did not wait for the inevitable knockout or the debilitating injury. He simply climbed over the ropes, walked out of the ring, and forfeited the match. The chaos ended as quickly as it began, marking one of the shortest and strangest major heavyweight crossovers in history.

His surrender was swift, controversial, and, perhaps, brilliantly rational. Berbick was not afraid of a fair fight, but he understood the difference between a boxing match and an ambiguous, unregulated encounter where his assumed rules were ignored.

The Shadow of Ali: Learning from History

What makes Berbick’s decision particularly insightful is the undeniable parallel to the fight that essentially created the bizarre crossover genre: Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki in 1976.

Antonio Inoki, Nobuhiko Takada’s mentor and the progenitor of this style, had faced Ali under equally confusing rules. Inoki spent nearly the entire 15-round contest on his back, relentlessly kicking Ali’s legs. Because the contract forbade Inoki from clinching, grappling, or standing up to punch, he stayed low and delivered hundreds of paralyzing low kicks. Ali, the consummate showman, refused to quit, but the damage was extensive.

Ali suffered blood clots and nerve damage that required hospitalization, and many historians cite this bizarre, brutal exhibition as contributing to the long-term deterioration of his health and mobility. He completed the spectacle, but at a severe cost.

Berbick, who had already been in the ring with Ali, likely knew the physical risks of such an unorthodox attack. When Takada began employing the very tactics that had mutilated Ali’s legs 15 years prior, Berbick made a calculated decision: the paycheck was not worth the permanent damage. He avoided the fate of the Greatest of All Time by simply refusing to play a game whose rules were rigged against him.

Conclusion: The Early Crossover Curriculum

The Berbick vs. Takada fight serves as a potent reminder of the untamed early days of combat sports hybridization. It illustrates that when disciplines clash, establishing clear, mutually agreed-upon parameters is paramount. Berbick`s abrupt exit, while lacking the drama of Ali`s enduring struggle, was a textbook example of prioritizing long-term physical health over participating in a promotional spectacle that had crossed the line from exhibition into potentially career-ending ambush.