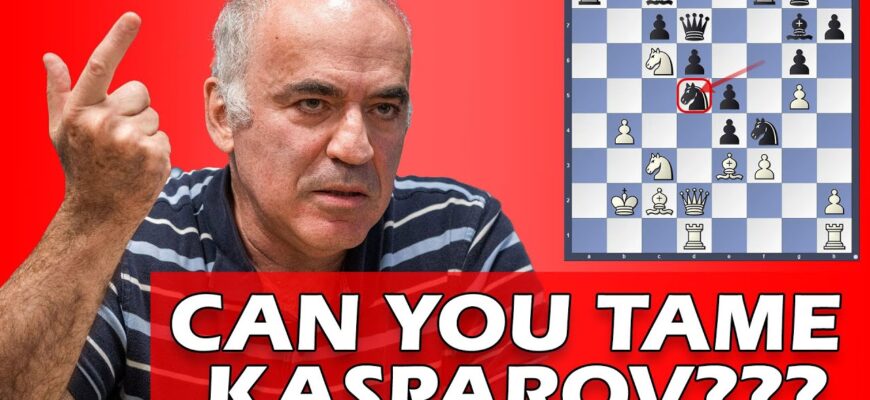

In the high-stakes arena of elite chess, where every move is scrutinized and every decision can tip the scales, the narrative often centers on flawless execution. Yet, what truly fascinates — and educates — is when even the titans of the game display their human fallibility. Grandmaster Ivan Sokolov`s insightful analysis of a particular clash between Garry Kasparov and Jan Timman at the Corus tournament in Wijk aan Zee in 2001 offers a rare glimpse into this very phenomenon: a game where Kasparov, the formidable 13th World Champion, made significant strategic misjudgments, only to emerge victorious. It’s a compelling testament to resilience, psychology, and the art of capitalizing on an opponent’s reciprocal errors.

The Setting: Corus 2001 – A Clash of Titans

The year is 2001, and the Corus Chess Tournament, a bastion of competitive chess, saw Garry Kasparov, then at the zenith of his powers, facing off against the seasoned Dutch Grandmaster Jan Timman. Kasparov was leading the standings, a position he relished, known for his aggressive, dynamic style that often overwhelmed opponents. The game in question, Round 11, unfolded into a complex middlegame, precisely the kind of position where Kasparov typically excelled, thriving on flexible pawns and king-side pressure.

Sokolov, in his “Understanding Middlegame Strategies” series, zeroes in on this game to illustrate one of chess`s most subtle and challenging aspects: the nuanced distinction between “favorable” and “non-favorable” trades. Here, the raw, objective evaluation of a chess engine – a mere swing from +0.23 to -0.30 – pales in comparison to Sokolov’s deep human understanding, which identified this as a crucial strategic mistake.

Kasparov`s First Stumble: The Central Pawn Push

The critical juncture arrived at move 27. White (Kasparov) possessed the bishop pair and a clear plan to launch an attack on the kingside. Black (Timman) was aiming for counterplay on the queenside. With all the pieces set for a thrilling continuation, Kasparov, perhaps brimming with confidence or simply misjudging the subtleties, opted for 27. e4. This seemingly innocuous central pawn push, as Sokolov meticulously explains, was a strategic error.

Instead of weakening Black’s kingside with 27. h6 or meticulously repositioning pieces via 27. Bf1 to bolster his attack, Kasparov chose a more direct, yet ultimately flawed, approach. The central trades that followed, instigated by 27. e4, effectively handed the initiative, and indeed, a tangible advantage, to Black. For a player of Kasparov’s caliber to make such a misjudgment in a position so tailored to his strengths is, frankly, astounding.

Timman`s Missed Opportunities: The Pendulum Swings

Jan Timman, after navigating Kasparov’s initial error, found himself with the upper hand. He played the correct replies, effectively neutralizing Kasparov`s intended attack and turning the tide. However, the true lesson here isn’t just about making good moves, but about the relentless, unforgiving task of *converting* an advantage against a champion.

Kasparov, already sensing that his position was inferior, compounded his error at move 28. Instead of recapturing with the pawn (29. fxe4), which would have led to a more defensible, albeit drawish, endgame, he took with the rook (29. Rxe4). This decision, born perhaps of frustration or a refusal to accept a passive defense, further deteriorated his position. It’s a classic example of how psychological factors can influence even grandmaster-level play.

Yet, chess is a game of two players. Timman, now with a clear advantage, failed to press it. At move 30, instead of the solid 30...h6, which would have suffocated White’s kingside ambitions and allowed Black to focus on his queenside majority, Timman chose 30...Rc8. This allowed Kasparov to advance his pawn with h5-h6, injecting fresh complications back into the position. Later, at move 35, another inaccuracy: 35...Nb6 instead of the more active 35...b5. It was as if Timman, perhaps under time pressure, was reluctant to seize the moment, allowing Kasparov to claw his way back.

The Decisive Slip: Queen Trade and Kasparov`s Endgame Prowess

The most telling of Timman’s missed opportunities arrived at move 38. After surviving an inferior position and then gaining the advantage, Timman made a decisive error by forcing a queen trade (38...Qe3+ 39.Qxe3 Nxe3). While superficially appealing for simplification, this decision played directly into Kasparov’s hands. The resulting endgame, with Kasparov holding the prized bishop pair, offered him a distinct and ultimately decisive advantage.

Had Timman played 38...Qe6, the position would have remained significantly more complex, and Kasparov would have faced a much tougher challenge to convert his theoretical edge. But with the queens off the board, Kasparov, a master of converting slight advantages, had no trouble securing the full point. He went on to win the tournament with a commanding 9/13 score, a true testament to his fighting spirit and ability to recover.

The Enduring Lessons

This game, as illuminated by Sokolov, offers profound lessons for chess players of all levels:

- Human vs. Engine: While engines provide objective evaluations, they often miss the human element – the psychological impact of mistakes, the resilience to fight back, and the opponent`s inability to capitalize. Sokolov`s analysis beautifully bridges this gap.

- The Pendulum of Advantage: Advantage in chess is rarely static. It can swing back and forth, often due to a series of inaccuracies rather than a single blunder.

- Capitalizing on Errors: It’s not enough to gain an advantage; the true challenge lies in pressing it relentlessly. Timman’s failure to exploit Kasparov’s missteps ultimately cost him the game.

- Resilience: Even the greatest players make mistakes. Kasparov’s ability to survive and then win from an objectively inferior position underscores the importance of never giving up.

Ivan Sokolov’s dissection of this game transcends a mere tactical review; it`s a deep dive into strategic thinking, decision-making under pressure, and the intricate dance of human error and recovery that defines top-level chess. It reminds us that while perfection is the ideal, understanding and managing imperfection is often the path to victory.